Originally published by Elise Margaritis on 30 Jun 2022.

On the north-eastern edge of the Northern Territory, Arnhem Land is an ancient wilderness spanning almost 100,000 km2. A tapestry of magnificent landscapes, Arnhem Land is rich in Aboriginal culture, native wildlife and what I can only describe as a powerful, spiritual magic.

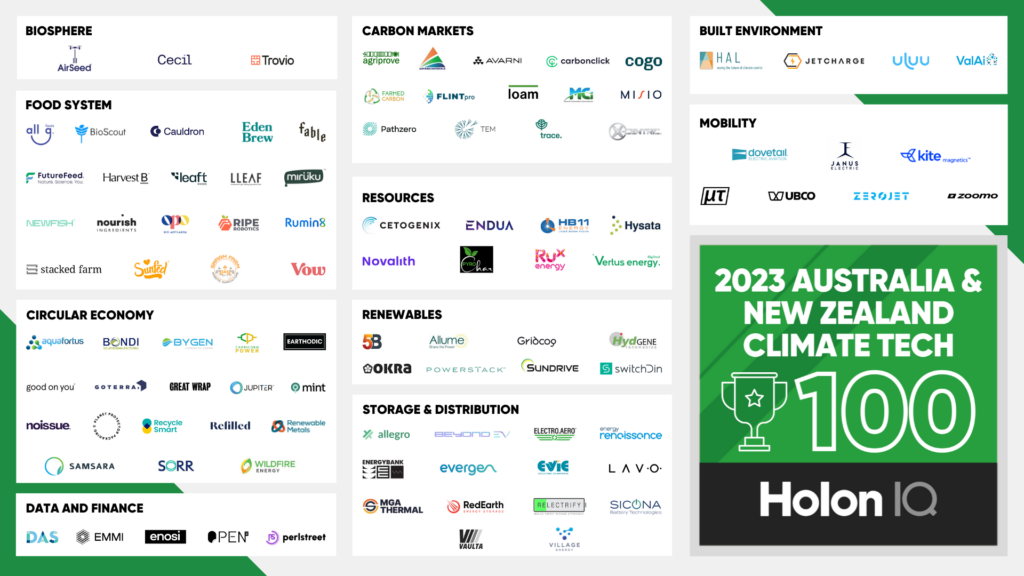

I had the immense privilege of visiting Arnhem Land last week at the invitation of the Karrkad Kanjdji Trust (KKT), a not-for-profit philanthropic organisation dedicated to preserving Indigenous culture by supporting community, education and employment. TEM has recently become a donor of KKT, supporting women rangers who are caring for country across Arnhem Land. I spent time on country experiencing the positive impacts of KKT and Arnhem Land Fire Abatement Northern Territory Limited (ALFA), an Aboriginal carbon business that partners with community ranger programs to deliver wildfire prevention projects that produce carbon offsets for TEM’s clients.

Hina and Elise ready to board their tiny plane.

Our journey began in Darwin. My colleague and friend Hina proved to be a perfect travel companion, as evidenced early on when she held my hand tightly while our little plane no bigger than the average boardroom table was buffeted across the 1.5 hour flight into Maningrida. The spectacular views distracted from the fear and we quickly started to see smoke rising up from early burns (sometimes called cool burns) across the land. Small streams of smoke twirling up to the heavens from little burns, larger plumes forming smoke clouds from big ones. On our approach to Maningrida we saw a burn stretching across the landscape for kilometers – it was awesome.

‘Look at all those ACCUs’, Hina said (Australian Carbon Credit Units).

Traditional fire management is conducted early in the dry season where cool, quick burns reduce the fuel load on the ground, preventing wildfires later in the season. These are low-intensity fires, described as a ‘tool for gardening the environment’. They burn low to the ground, are self-extinguishing and cool enough to allow young trees to survive and keep grass seeds intact for regrowth. A wildfire in comparison burns hot, up to the tree canopy destroying everything in its wake – flora, fauna, rock art – nothing is spared.

When we landed in Maningrida the first thing that struck me was the beautiful red earth. The colour a result of the high levels of iron oxidising in the soil – so old is the soil that it is rusting.

The Raindance machine – an aerial incendiary machine that dispenses pellets from the air.

We were met at the airstrip by Alex, a Bawinanga Djelk Ranger Manager who took us to the ranger shed a short drive away. There he introduced us to the other rangers who were taking their lunch break. I was excited to show the team some photos from the air of the little fires we saw and the mammoth one that stretched the landscape. The ranger Samuel smiled and said, ‘Oh yeah I did that one this morning’.

The burn stretches for kilometres across the horizon.

He told us they’d jumped in the chopper earlier and created the landscape-scale firebreak using the Raindance machine (an aerial incendiary machine that drops pellets from the chopper that ignite on the ground to start the fires). He estimated that particular burn required 4000 individual pellets dropped at intervals across a carefully mapped aerial route. The pellets contain condy’s crystals which when injected with glycol, ignite after a few seconds and then start a fire when they land on the ground.

We were introduced to Mark who runs the newly established accredited fire management training arm of ALFA. ALFA was created by Aboriginal landowners to support their engagement in the carbon industry. They support their partner Aboriginal ranger programs by providing funding to work with Traditional Owners to undertake fire management, on the job training, accounting for the carbon abatement and bringing the carbon offsets (or ACCU’s) to the market for our clients like Qantas, Australia Post, Lion and many others.

Mark mentioned that Arnhem Land has been approached by drone operators who could effectively conduct the aerial burning remotely. However, people are not interested, since this would take away from the fundamental element of the program – allowing Traditional owners to connect to their country and continue their cultural fire management obligations. Fire is such an intrinsic part of Indigenous culture, a tool to manage country. The people conducting it cannot be replaced.

The choppers usually contain three people: a pilot (often with mustering experience, adept with flying low and understanding the wind), a Traditional Owner or Djunkay (respectively with management obligations inherited from their father or from their mother’s country) and an experienced Aboriginal ranger operating the Raindance machine.

In the sky above us a couple of birds circled elegantly. The rangers explained they were Black Kites – birds that, like the rangers, also like to light fires. As flames sweep across the savanna, Black Kites watch for prey like insects and lizards that flee the fire. But they also create their own fires by picking up burning twigs and carrying them away from the original fire where they’ll drop them and wait for escaping prey. Setting a new area ablaze allows the bird to feed in a space away from rival predators.

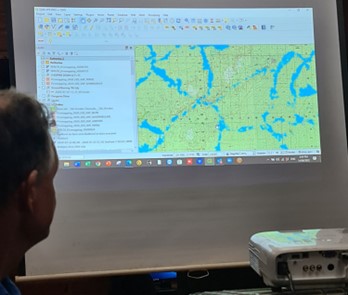

The rangers spend much of their time mapping out a mosaic of firebreaks across the landscape in order to protect natural and cultural assets and block or contain approaching wildfires should they ignite later in the season.

In addition to reducing emissions from wildfires, traditional burning also prevents fires from destroying rock art galleries, wildlife and endangered flora like stands of anbinik trees (Allosyncarpia ternate) – a proto eucalypt especially significant to Aboriginal culture.

My six-year-old son Max made it very clear to me that I should not bother returning home without a photo of a crocodile. When I told Alex he said we could fix that straight away since he had a baby croc in the tank. Part of the rangers’ work is to collect crocodile eggs. It’s a dangerous undertaking since the mother crocs can understandably be protective, territorial and aggressive. But remarkably, only 1% of croc eggs hatch in the wild due to a range of natural phenomena. Collecting these eggs and incubating them can lift this hatch-rate to around 80%. The eggs are then sold to crocodile farms for an additional income to support the ranger program.

Sophisticated technology maps out strategic locations for these cool burns.

Later in the afternoon we jumped in the 4WDs for our drive out to Djinkarr outstation where we’d be camping for the next couple of nights. The roads were red and rough, we quickly lost mobile coverage but gained a plethora of beautiful bird species flying through the trees. Stacey from KKT was a wealth of information (and an avid bird photographer!) answering my many questions. She told me about how she was given a skin name by a little girl who adopted her. When I asked about the origin of the name ‘Arnhem Land’, thinking it was a romantic anglicised version of a local name, I learned it came from Dutch ship the ‘Arnhem’ that sailed into the area in 1623.

It’s difficult to navigate these wide, rustic roads so the team from KKT had cleverly placed a chair on the side of the turn to Djinkarr. We arrived, set up camp and prepared dinner. Jen, the CEO of ALFA joined us.

I have never camped this far into the wilderness. It was magnificent, breathtakingly beautiful. And I did not sleep a wink. Every snapped twig, animal call, crackle of leaves sparked my senses. I’m certain I heard footsteps circling my tent. It didn’t help that Dean, the Traditional Owner on who’s country we were camping excitedly described the 47 species of tarantula that called his country home. One newly found species of which burrows tunnels and travels underground… no, no sleep tonight.

Our breathtakingly beautiful campsite.

In the morning I described to my camp mates the spectacular sounds that kept me awake, including the footsteps. I was met with incredulity.

So after breakfast we headed to the river for a tour on the boats the rangers use to patrol the waters. Not five minutes into the ride ranger Grestina spotted a croc swimming gracefully in our direction. I was elated and the croc was enormous! Perhaps it was the noise of the engine but she quickly sunk beneath the surface and we continued on our way. Captain Alex recounted a story of when he was fishing for barramundi. He was reeling the fish into the boat when a croc leapt up out of the water to steal the fish snapping inches from Alex’s fingers. But Alex won the fish and the croc swam off to find another meal. This is wild country indeed.

The croc elegantly surfaces before disappearing once again.

Soon we pulled the boats up to a sandy patch of riverbank and disembarked onto the floodplains. There were patches of cracked earth between the grasses, evidence of the buffaloes that are roaming wild across the land. Research suggests more than 160,000 of the introduced buffalo are marching across the floodplains destroying once thriving ecosystems and important hunting grounds and cultural sites for Traditional Owners. The herds trample waterways and destroy habitats for crocodiles and long-neck turtles.

Serendipitously, eagle-eyed Grestina shouted ‘buffalo in the water!’. Across the river a buffalo indeed was swimming downstream, horns glistening wet in the sun, attempting to come ashore but thwarted by our boats. All of us quietly hoped the croc would come along and find her meal. But it was not to be as the buffalo found foot on a nearby bank.

Thrilled by the unusual encounter, we boarded the boats and headed back to the dock. On the way Grestina spotted a sea eagle perched in a tree. We pulled up and she threw a piece of chicken into the air. The eagle flew down from its perch in a spectacular display. I stand, camera ready, on the rocking boat in awe of the connection Grestina has to nature. She sits at the bow of the boat, hand signaling to Alex which way to steer but all the while soaking up the magic of the land and water, appreciating it, nurturing it, and kind enough to share our eagerness when spotting an animal that she likely sees every day.

We returned to the ranger base, had lunch then jumped back into the 4WDs to head out to participate in a cultural burn. This was it. The reason we had come all this way and we were excited.

We drove out to Rocky Point with the rangers, one of whom was a Landowner and another Djunkay for this country, which had a breathtaking view of the ocean. On the horizon, people on a boat were spear fishing. The sun made the water sparkle, we were captivated.

The rangers then handed each of us a box of special matches used to light the fires. They were thicker and longer than regular matches. We then walked along the red dirt road, striking the matches and throwing them into the dry grass which would quickly ignite, burning fast, leaving a black shadow in its wake. The rangers also showed us how to use the drip torches, cans filled with a mixture of diesel and unleaded petrol. Ignited at their tip, we dripped the fire liquid from the cans as we walked along the path. The experienced rangers would take their drip torches deeper into the woodlands to ignite fires within. We quickly set fire to the brush which you could see was burning fast but also extinguishing itself as it consumed the grass. Grestina showed us how to take a dry fallen leaf from the palm trees, light it and then ignite the tree to create a faster burn. It was immensely satisfying, clearing the land of the dry grass and fallen leaves. You could see how this method cleared the fuel load on the ground that would prevent wildfires from taking hold and destroying everything in the landscape. Bugs were crawling away, birds had time to flee, animals high in the canopy were not affected at all.

Elise and Hina participate in traditional fire management, where cool, quick burns reduce the fuel load on the ground, preventing wildfires later in the season.

It was mesmerising. We continued along the path, striking matches, dripping fuel, taking photos of each other performing this ancient ritual that has been conducted for thousands of years but for us felt so novel. So dangerous. So fun.

We return, exhausted but exhilarated. An experience once unimaginable.

Covered in ash, smoke clinging to our clothes and hair we once again boarded the 4WDs and I remarked to my car mates as I drank from my water bottle that you’ve never really been thirsty until you’ve been traditionally burning in Arnhem Land’s 30-degree heat, with a dry throat and watering eyes. And I’d never felt so exhilarated. So fortunate to experience a fundamental part of Aboriginal culture. Such a normal thing but which for us coming from down south felt so adverse to what we’ve been taught. In the summer our bushfires are terrifying. We vilify fire bugs. So to be up here, gleefully striking matches to create fire in a way that is helpful to the landscape was strange. But we quickly understood and saw with our own eyes how these self-extinguishing fires do good. We returned to camp, exhausted and desperate to wash the grit from our faces and honestly that shower was the best one of my life.

At dinner we were joined by the Traditional Owners of the land on which we camped: Dean and his son Randy. Olga from the Nawarddeken Academy (that offers community-driven education in remote Indigenous communities) brought along two spectacular barramundi that her sons caught in a nearby river. Randy cooked the fish on the fire, placing them on leaves he pulled from the wattle tree that stood beside the camp. He told me there was a male and female fish. I asked how he knew so he described how the female was wider in the middle and her head shape was different. He pointed out the ironbark tree to my left, which is hollow in the middle on account of the termites eating out the center. The tree is used to produce hunting tools. He told me of the wattle tree flowers, that when they bloom it’s a signal to the people that it’s time to go fishing. Nature sets the timing of the seasons (in Indigenous culture there are six seasons, not four) and the activities conducted within. I felt a wrenching in my gut when I thought of how climate change is affecting these signals.

As the fish cooked we talked about how the spirits of ancestors wait on country for their family to return and take care of it. Randy was immensely proud of his 4-year-old granddaughter who could name every one of their long line of ancestors and the stories that went along with them. Storytelling is a fundamental part of culture and the sharing of knowledge. Randy said it was difficult for families who lived in town to return to country because there was no transport and no way to move to and from in order to access supplies. The national requirement for children to be enrolled in school also complicated the ability for families to be on country. So, he planned to run a small community bus from town out to homelands to encourage people to return to their land.

When dinner was ready Randy played some traditional music on his phone. It was enchanting. And the barramundi was the best I had ever tasted.

Later that night as we said goodbye (or ‘bo bo’ in the local language), Randy told me I had a great responsibility now since I had experienced life the way his family lived it. My role was to be like the wattle tree – to spread the seeds of knowledge, throw them to the wind with my family, friends and colleagues. He said if I did that, the seeds would eventually come back to his country in fruition. I was struck silent by the poetry, the teaching and the weight of my newfound responsibility.

In the morning my camp mate Peter described that he too heard footsteps while he slept and when he looked outside he saw what he thought was a dingo circling the camp. My perceptions from the night before were vindicated!

We visited the Babbarra Women’s Centre who produce exquisite textile works including clothes, bed sheets and tea towels with designs telling the ancestral stories of West Arnhem Land culture and wildlife. The enterprise creates employment opportunities for women in the community and local artists. In fact Jen used to work here, having lived in Maningrida for several years with her young family.

The town itself presented the complexity of living in remote Australia. The housing situation can only be described as at crisis point. Overcrowding, particularly in the wet season when people cannot easily travel to outstations, exacerbates issues including the spread of preventable disease, sleeping issues and food insecurity. Due to the remoteness of the area, and difficulty accessing materials and trades, one average-sized new house would cost many hundreds of thousands of dollars to build. There is a desperate need for government or philanthropic funding.

We have no right to call Australia The Lucky Country when our First Nations peoples are suffering like this.

I observed many abandoned vehicles in front yards and beside the road. The rough terrain is unsuitable for small cars, which are affordable but quickly break down. The cost of parts and mechanical services are exorbitant so the cars are left to rust, leaving people isolated and unable to travel to their homelands. Randy’s community bus service will be vital.

Job opportunities are rare. However, being a ranger is highly respected. A mix of Government, philanthropic and carbon income provides the resources to care for their country enabling people to earn an income, have access to training and development and wear their uniforms with pride. It was clearly evident how the fire projects, and the income from the sale of ACCUs, were delivering extraordinary positive impacts to local communities, families and individuals.

From there we toured the local gallery, Maningrida Arts Centre. A unique and valuable cultural collection of national and international significance. We had the rare opportunity to see a local artist at work in the back room as he painted his wooden sculptures. I was taken by two carved wooden Mimihs created by young local artist Jemma Yibbruruana. The Mimih are fairy-like spirits with extremely thin and elongated bodies that live in the cracks of the Arnhem escarpment. They are said to have taught Kuninjku people many of their characteristic ways of cooking, hunting and dancing. They also created much of the region’s early rock art. I bought two Mimihs that reminded me of my children, because like my children the Mimihs are described as being very cheeky. I couldn’t fit them in my luggage so have arranged to have them posted.

When I arrived home I discovered the SD card on my phone that stored all of the photos and videos from my trip had become corrupted. My husband is working tirelessly to restore them but I can’t help thinking, as suggested by Hina, that this is a cheeky prank by my new Mimih friends, annoyed that I didn’t find a way to immediately bring them home with me.

So now as I write this account I do it in thanks for the tremendous opportunity afforded to me by my team at TEM, in appreciation of the vital work conducted by ALFA and the KKT, but mostly I do it for Randy. Because I do want to be like the wattle tree, sharing the seed of knowledge. And it reminds me of the time years ago when I agonised over designing the TEM logo and finally decided on the concept of the dandelion with its seeds about to take flight. Because TEM is a business cemented in the sharing of information in order to empower positive actions. There is tremendous hurt in our Indigenous communities, but their spirit, strength and connection to country is creating a lot to be hopeful for. And like the rangers, we can take that spark of hope and ignite a fire of powerful change. For people, for biodiversity and for the planet.

If this story inspires you to make your own contribution to the Arnhem Land rangers, please visit KKT and ALFA to learn more.

These burns stretch for kilometres, creating mosaics in the landscape.